About Norman Collins

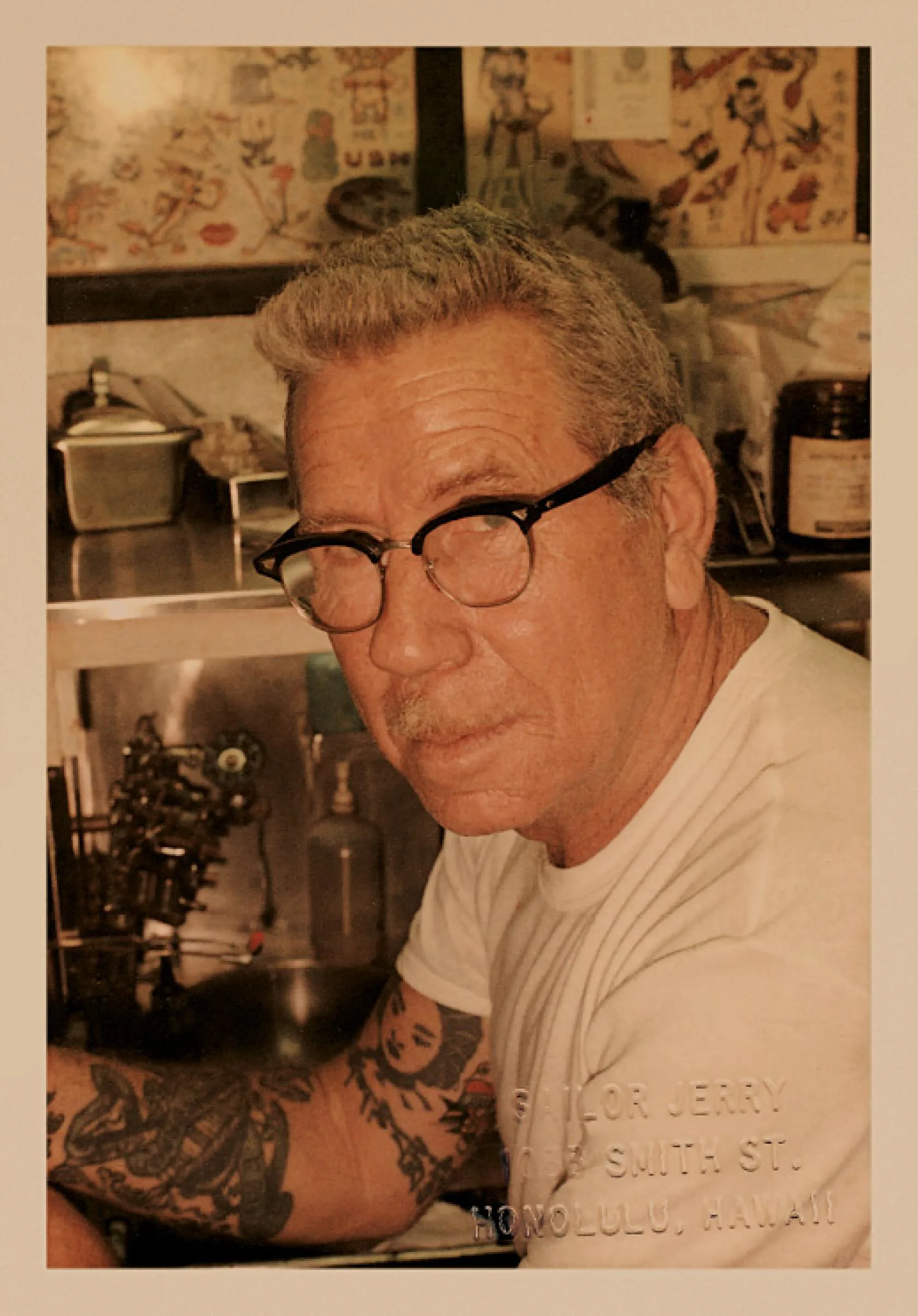

SAILOR JERRY WAS BORN NORMAN COLLINS, BUT CHOSE TO DEFINE HIMSELF ON HIS OWN TERMS. HE SIMPLY WASN'T ONE OF THOSE PEOPLE BORN TO LIVE A MIDDLE-OF-THE-ROAD LIFE AND HE KNEW IT. BACK IN THE 1920'S, WHEN COLLINS CAME OF AGE, TATTOOING WAS AN EXPRESSION THAT BELONGED TO AN EMERGING AMERICAN COUNTERCULTURE. IT WAS A MARK OF NOT BLINDLY FOLLOWING THE MAINSTREAM - OF CHOOSING TO LIVE OUTSIDE THE LINES.

About Norman Collins

SAILOR JERRY WAS BORN NORMAN COLLINS, BUT CHOSE TO DEFINE HIMSELF ON HIS OWN TERMS. HE SIMPLY WASN'T ONE OF THOSE PEOPLE BORN TO LIVE A MIDDLE-OF-THE-ROAD LIFE AND HE KNEW IT. BACK IN THE 1920'S, WHEN COLLINS CAME OF AGE, TATTOOING WAS AN EXPRESSION THAT BELONGED TO AN EMERGING AMERICAN COUNTERCULTURE. IT WAS A MARK OF NOT BLINDLY FOLLOWING THE MAINSTREAM - OF CHOOSING TO LIVE OUTSIDE THE LINES.

Collins left home as a teenager to travel the country by hitchhiking and train hopping. He wasn't alone. At that time, a substantial number of Americans, young and old, were bypassing the so-called American Dream for a different kind of existence. For some, this was prompted by hardship and necessity. But for Collins and others like him, it was about wanderlust and freedom. They traveled by freight train, took temporary work and camped along the way. This was when Collins started learning his craft, working primitively with only a needle and black ink, creating designs freehand, one poke at a time.

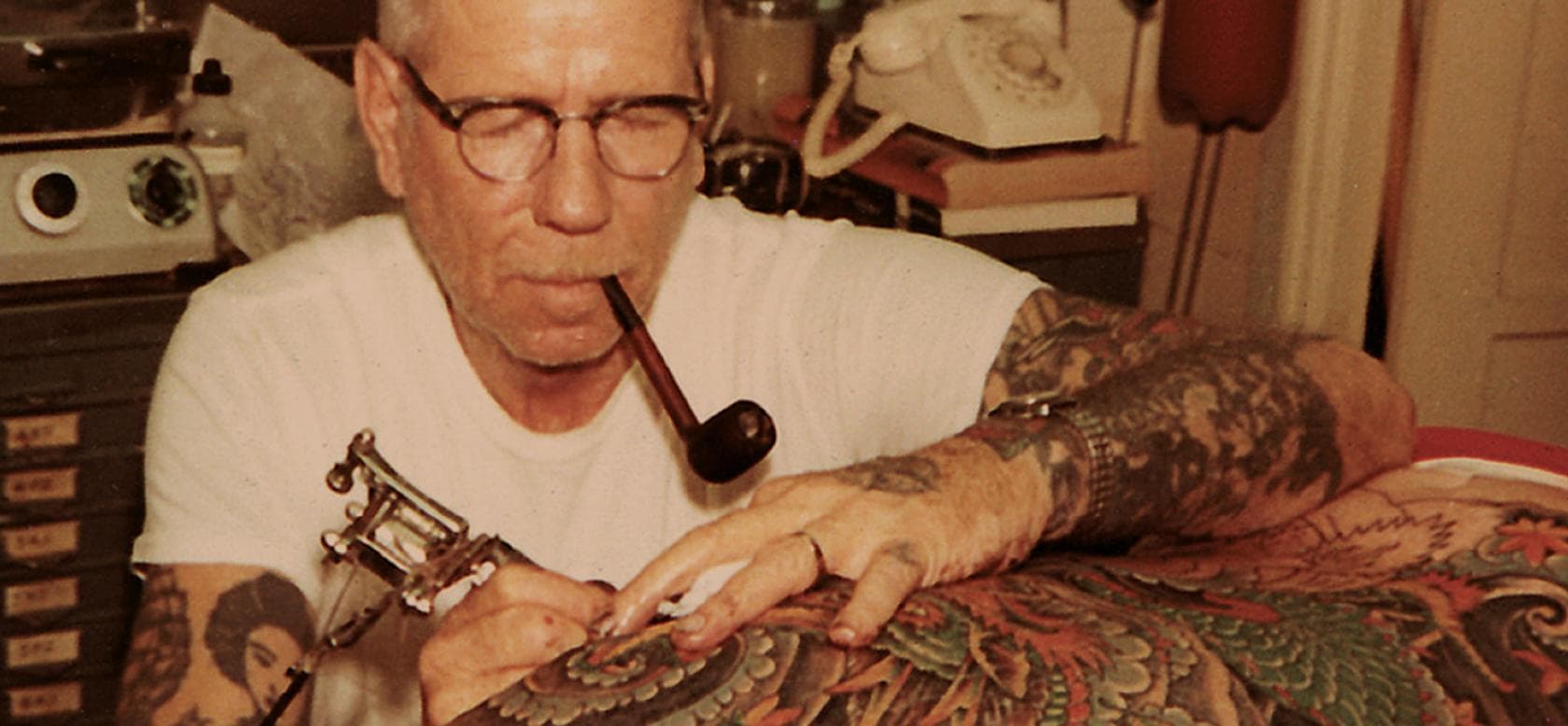

He eventually landed in Chicago and two things happened that changed his life. One, he hooked up with local tattoo legend, Gib 'Tatts' Thomas, who taught him to use a tattoo machine. (For practice, he paid bums with cheap wine or a few cents to let him tattoo them). The second was joining the Navy. The United States Navy was a place where a young man who'd been crossing the country on freight trains could up the ante on his adventure and cross oceans. It was during this time, Collins developed a lifelong love of ships. He would eventually earn master's papers on every kind of vessel you could get tested for.

Collins left home as a teenager to travel the country by hitchhiking and train hopping. He wasn't alone. At that time, a substantial number of Americans, young and old, were bypassing the so-called American Dream for a different kind of existence. For some, this was prompted by hardship and necessity. But for Collins and others like him, it was about wanderlust and freedom. They traveled by freight train, took temporary work and camped along the way. This was when Collins started learning his craft, working primitively with only a needle and black ink, creating designs freehand, one poke at a time.

He eventually landed in Chicago and two things happened that changed his life. One, he hooked up with local tattoo legend, Gib 'Tatts' Thomas, who taught him to use a tattoo machine. (For practice, he paid bums with cheap wine or a few cents to let him tattoo them). The second was joining the Navy. The United States Navy was a place where a young man who'd been crossing the country on freight trains could up the ante on his adventure and cross oceans. It was during this time, Collins developed a lifelong love of ships. He would eventually earn master's papers on every kind of vessel you could get tested for.

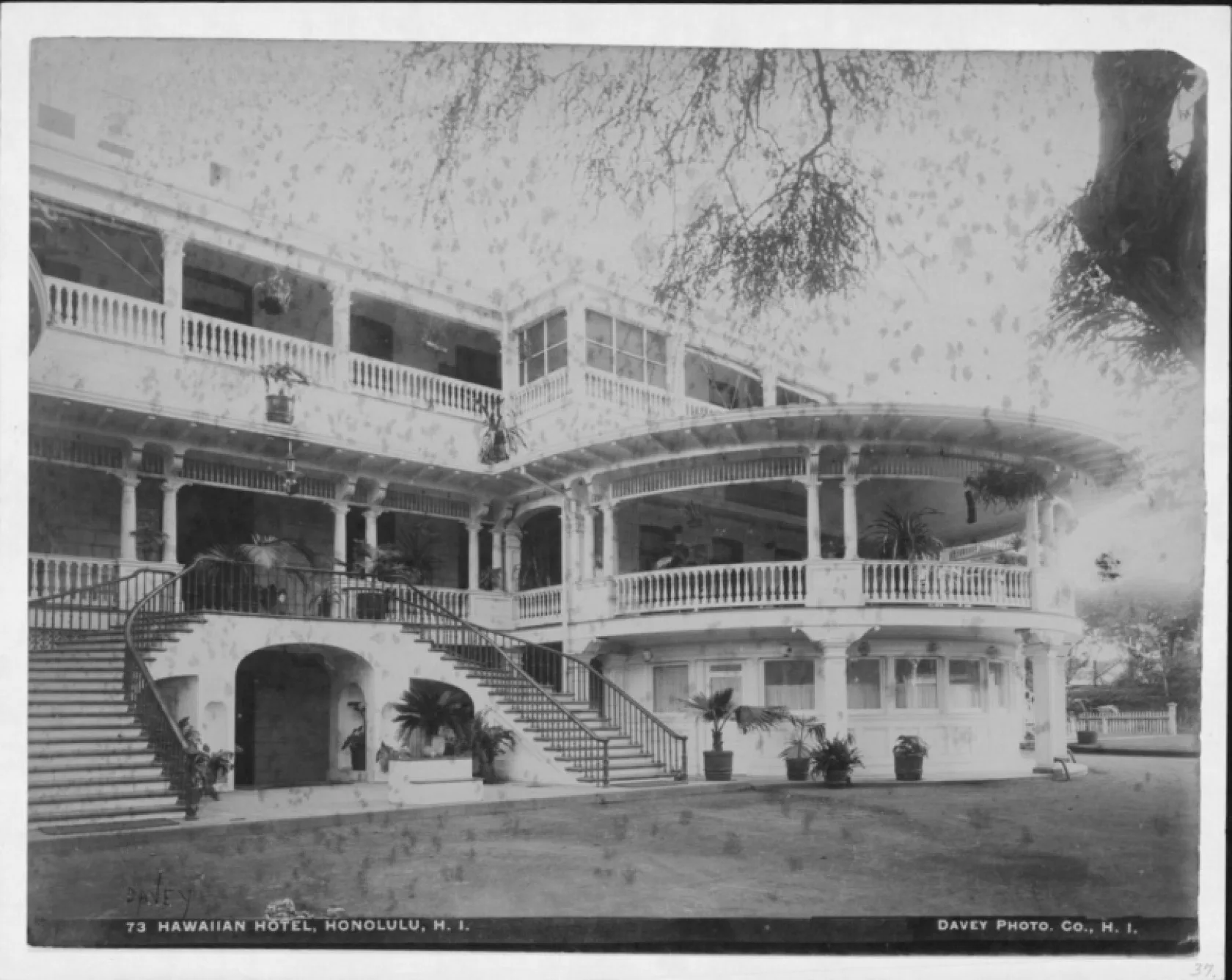

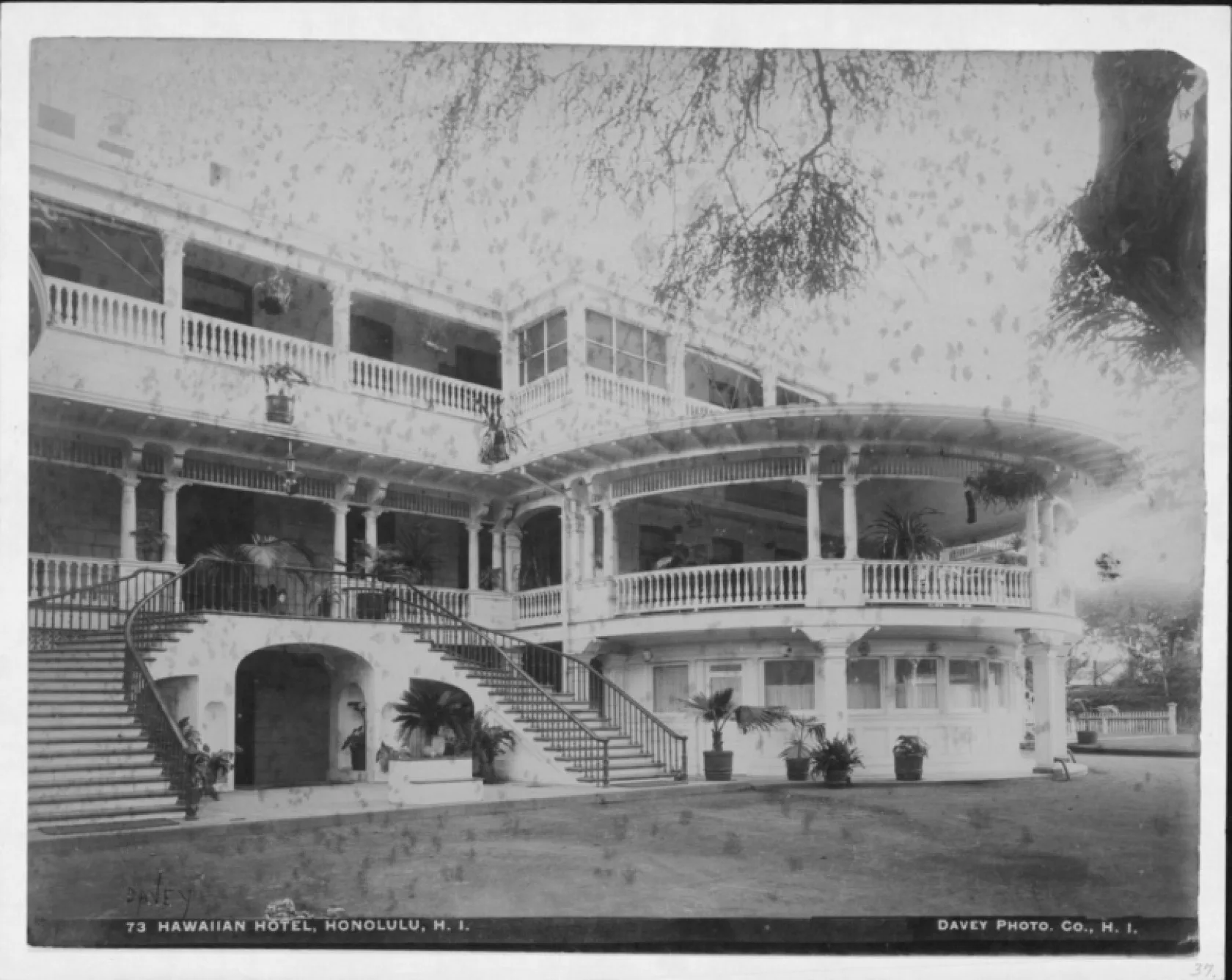

When Collins mustered out of the Navy, he settled in Honolulu. Back then, Hawaii was backwater cluster islands, but within a few years, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and everything changed. At the height of WWII, over 12 million Americans served in the military and, at any given moment, a large number of them were on shore leave in Honolulu. The circumstances of war fed a cross-section of American men into environments that usually only existed on the fringes – places like Honolulu's Hotel Street, a district comprised almost exclusively of bars, brothels and tattoo parlors. This was where Collins, as Sailor Jerry, built his legacy.

WELCOME TO HOTEL STREET

WWII WAS A GREAT EQUALIZER. IT WAS A TIME WHEN SERVING IN THE MILITARY BROUGHT TOGETHER EVERY LAYER OF SOCIETY. IT WAS A RARE TIME IN AMERICAN HISTORY, WHEN PEOPLE FROM ALL STATIONS OF LIFE ENDED UP ON THE SAME SHIPS, THE SAME PLATOONS, THE SAME BATTLEFIELD — AND IN THE INSTANCE OF THE HOTEL STREET DISTRICT IN HONOLULU, THEY ENDED UP IN THE SAME NEIGHBORHOOD ON SHORE LEAVE.

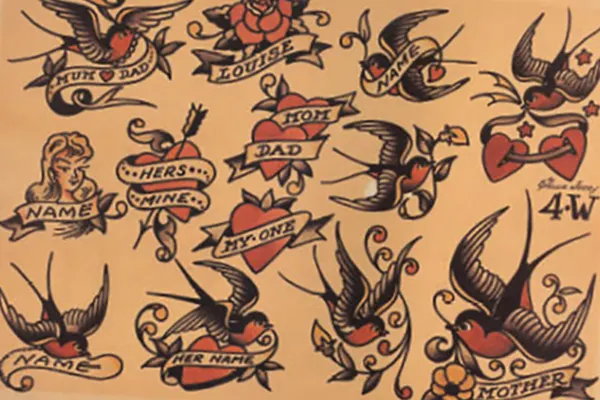

Soldiers and sailors wanted to grab all the experiences they could before they shipped out. Whether a man was raised in a Park Avenue mansion or a farmhouse in Alabama, while on shore leave, he was fixated with one of three things (or most likely all three of them). To paraphrase the words of an iconic Sailor Jerry tattoo (as requested by our lawyers), these soldiers were out to have some drinks, enjoy the company of women and get tattooed. Lines for bars were so long that you had only minutes to finish your drink before having to make room for the next guy. The mix of shenanigans and bravado that characterized the mindset of an American serviceman on shore leave is a deep thread in Jerry’s art. From “Man's Ruin,” an image of a vixen in a cocktail glass surrounded by a dice, cards and dollar signs – to a picture of a bloody knife sticking though a heart with the words “Death Before Dishonor” – Sailor Jerry's tattoos dealt with issues that were at once practical and elemental. Hotel Street may have been a place that would make a preacher blush, but it was also a place where truths were expressed. War, whether you're for it or against it, tends to filter out the crap and this is one reason why Sailor Jerry's work is so compelling.

COJONES AND ARTISTRY

"If you don't think you're man enough to wear a tattoo, don't get one. But don't try to make excuses for yourself by knocking the fellow who does!" Signed, "Thank you...Sailor Jerry," this note was placed prominently in Jerry's Hotel Street shop and it gives you some idea of the attitude that he brought to his work. He was aware that his clientele weren't miscreants just out to paint the town red, they were men serving a higher cause. Or as he put it, "The tattooed barbarians that live and die on world battlegrounds."

Ironically, Jerry was deeply influenced by the culture that started the war in the first place - the Japanese. The most proficient and sophisticated tattoo artists of the times were the Japanese masters known as Horis. He became the first Westerner to enter in regular correspondence with these masters, sharing techniques and tattoo tracings. By fusing American and Asian sensibilities, Jerry created his own style of tattooing - iconic and artistic, irreverent and soulful, radical and beautiful.

COJONES AND ARTISTRY

"If you don't think you're man enough to wear a tattoo, don't get one. But don't try to make excuses for yourself by knocking the fellow who does!" Signed, "Thank you...Sailor Jerry," this note was placed prominently in Jerry's Hotel Street shop and it gives you some idea of the attitude that he brought to his work. He was aware that his clientele weren't miscreants just out to paint the town red, they were men serving a higher cause. Or as he put it, "The tattooed barbarians that live and die on world battlegrounds."

Ironically, Jerry was deeply influenced by the culture that started the war in the first place - the Japanese. The most proficient and sophisticated tattoo artists of the times were the Japanese masters known as Horis. He became the first Westerner to enter in regular correspondence with these masters, sharing techniques and tattoo tracings. By fusing American and Asian sensibilities, Jerry created his own style of tattooing - iconic and artistic, irreverent and soulful, radical and beautiful.

In a sense, Jerry was always battling something, whether it was conventional thinking, the mediocrity of copycat tattoo artists or the government meddling into his affairs. He never knuckled under to anyone or anything. To quote from a letter Jerry wrote to protégé, Don Ed Hardy, commenting on a yin yang dragon design, “keep them fighting, it's the way that Yin Yang functions — if there is no opposition of forces there is no evolution of life!”

Jerry was continually frustrated by other artists (who he called “brain pickers”) copying his work. He refused to do big chest or back pieces on customers who had tattoos by artists he didn't respect. His letters to fellow tattoo artists are a testament to his devotion to the craft of tattooing. He goes over detail after detail, from techniques for shading to the “possibilities of tone and texture” to “crash” effects. Jerry was in a constant quest to deepen his own skills. “My slogan is,” he states, “I haven't done my best yet, only my best so far.”

Yet tattooing was just one dimension of Jerry’s life. He continued to pursue his maritime interests as captain of a three-masted schooner that toured the islands. He had his own radio show called Old Ironsides on KRTG during which he alternated between political rants and reading his own poetry. He taught himself to be an electrician, which helped him innovate his tattoo machines. He played in a jazz band. He toured around in a canary yellow Thunderbird and he was out on his Harley when he had the heart attack that would take his life (after collapsing in a cold sweat, he got back on his bike and rode home). The day before Jerry died, he wrote a letter to friend and fellow tattoo artist, Paul Rogers, joking that he was going to “down some ground seahorse meat, pulverized ratshit, snake skin, lizard eggs, dried snails and dried bat skin and by go we will see who is the best doctor in the end.” He asked that upon his death, his shop be passed on to his protégés, Don Ed Hardy and Mike Malone (aka Rollo Banks). If neither took the place over, Jerry left instructions it was to be burned to the ground. Malone took possession of the shop and ran it for almost 25 years.